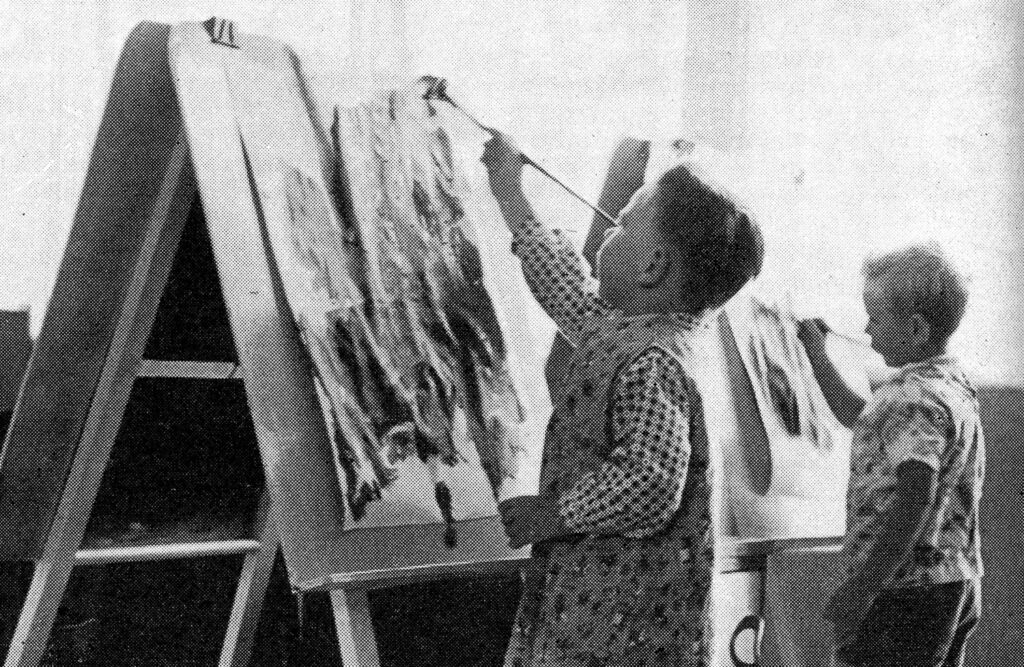

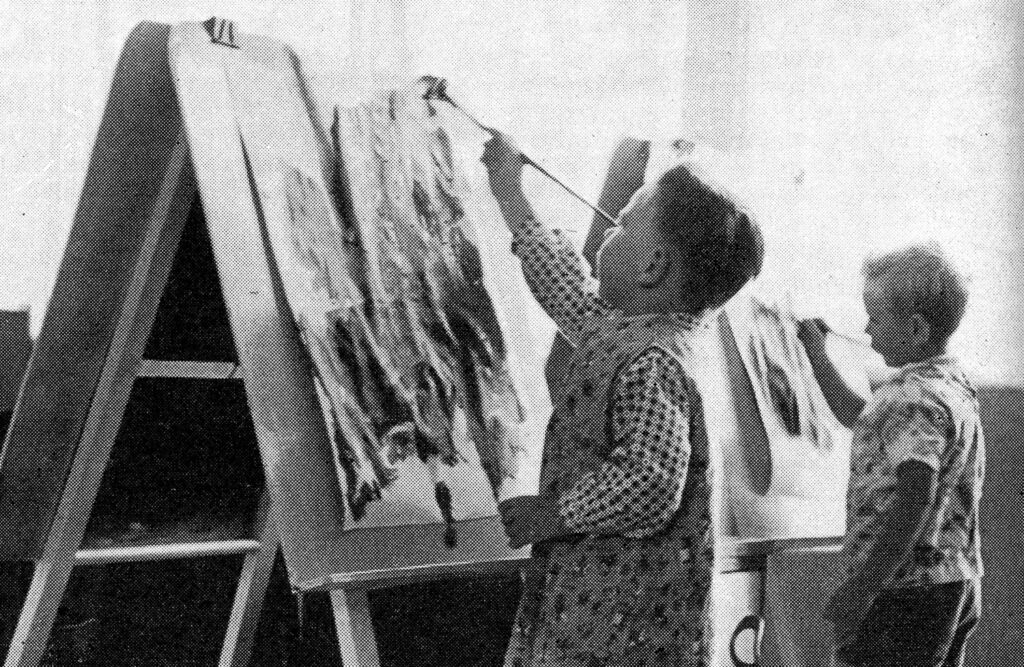

...some kindergartners...use as their subject matter the interest of the moment. This demands more from a teacher than any other method. It means a keen insight into the need of the moment, a quick understanding of its educational possibilities, a richly-stored mind upon which she can always draw a need, and a spontaneity and resourcefulness that is never at a loss under any circumstances. Such a teacher (though) will get better results than any other, because she literally follows the lead of the child.”

- Zoe Benjamin, Australian Kindergarten magazine, January 1915

- Reggio Emilia (Italy) – an approach to curriculum that recognises the social nature of learning and positions children as capable and powerful learners and provides a democratic context where children are able to participate in decision-making about their educational experiences.

- Emergent curriculum – this approach suggests that children learn best when curriculum is connected to their everyday lives and interests. Therefore, pedagogies must respond to different children in different contexts.

- Te Whāriki (New Zealand) – curriculum which emphasises the cultural nature of development and aims to value diverse cultural experiences, beliefs and expectations with respect to children’s development.

- Learning Stories (New Zealand) – valuing children’s ideas and ‘helping make their learning visible’.

- Early Years Learning Framework (Australia) – Belonging, Being and Becoming (introduced in 2009).

With the establishment of KU Family Programs to support vulnerable families, KU introduced a ‘family centred approach’ from the USA that involved not only providing programs for children with high support needs, but also offering specialised support programs to their families.

From the beginning of the new millennium, KU invested in strengthening pedagogical practice with Attachment Theory as a significant focus. This included staff exploring and implementing the Circle of Security and the Marte Meo approaches.

The new millennium also saw KU partner with The Mind Institute in California and the University of NSW to implement and research the implementation of the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) in its specialised service for children diagnosed with autism.

More recently, through its commitment to sustainability and the use of natural materials, KU educators have drawn on an ecological model of pedagogy that reveals children’s relationships with family, the early childhood service and community as interdependent with earth’s dynamic systems.

Throughout its 125 year history, KU has proven to be an innovator in curriculum, often being at the forefront in piloting particular approaches and drawing on contemporary methods and research from around the world.

“Educators professional judgments are central to their active role in facilitating children’s learning. In making professional judgments, they weave together their professional knowledge and skills; their knowledge of children, families and communities; their awareness of how beliefs and values impact on children’s learning and their personal styles and past experiences. They also draw on their creativity, intuition and imagination to help them improvise and adjust their practice to suit the time, place and context of learning.”

- Early Years Learning Framework, 2009